A Shocking Holiday

A few hours before you head out to Grandma’s for your family’s Christmas feast, everyone in the house is in a tizzy. The crock pot is going on the island in the kitchen, every light in the house is on, and your wife is in the master bathroom blow-drying her hair. You pick up the hand mixer to mash the potatoes, and you’re just about done when everything gets a little bit quieter. As you scramble to figure out what happened, you run to the laundry room and flip the breaker and the lights in the kitchen came back on! When you arrive back in the kitchen, your wife is standing there with her hair half done, looking puzzled. Did this outage affect her as well? Apparently so. You explain that the hand mixer must have pushed the breaker past its limit and ask if she can move her hair dryer to a new room to finish getting ready. She begrudgingly agrees.

Why would the hair dryer in the master bathroom and the outlets in the kitchen be on the same breaker? What makes this breaker stop working, and can you just get a bigger one? These are the questions you and your wife ponder once the holiday chaos settles. It’s clearly a pain to have to alternate work in the kitchen and someone getting ready in the bathroom at the same time.

If you read nothing else, please do not buy a bigger breaker unless you also run bigger wire to all the outlets.

For many, electricity is a scary abyss they never want to delve into. Yet when faced with a practical problem like this, a home project might land on your list, especially after you get the first quote from a professional electrician. There’s a reason they’re expensive, and I’m not saying you shouldn’t hire an expert. I’m merely trying to give you some understanding of how this works so you can decide if it’s something you want to tackle as a do-it-yourself project.

When a home is being built, the time crunch is severe. In recent times, home builders operate on extremely thin margins, so they have subcontractors bid on a fixed price rather than time and materials. This incentivizes the subcontractor to move quickly. When building a home, builders must follow the National Electrical Code (NEC), which sets the safety standards for electrical systems. Engineers and scientists determined the safety limits of electrical installations and published them as code. For example, the NEC recommends about thirteen outlets on a 20-ampere circuit, and you can generally put twenty-four 100-watt fixtures on a single circuit. Let’s assume you combine lights and outlets on the circuit, which is very common in residential settings. Let’s say six outlets and twelve light fixtures. Your bedroom probably doesn’t have six outlets or twelve lights. But the builder is faced with a dilemma: they’re within legal bounds to maximize this run of wire, and wire is expensive. Running a second circuit takes time and money. This room is on the way to that room, when looking from the attic, it’s just a straight line. So they add two or three extra outlets to your bedroom’s circuit. They don’t have to live with this decision, so they often don’t consider the functional problems it creates.

First Principles

To understand why that breaker tripped and why you can’t just up-size it, we need to talk about how electricity actually works. Don’t worry, it’s just four basic ideas.

Voltage is the “push” of electricity. It’s the potential energy available in your circuit. Your home outlets provide 120 volts (or 240 volts for big appliances). Think of it like water pressure in a hose, higher pressure pushes harder. Voltage is represented as V in equations.

Current is the actual flow of electricity through the wire, measured in amperes. If voltage is the push, current is how much is flowing. More amperes means more electricity moving through that wire. This is represented as I.

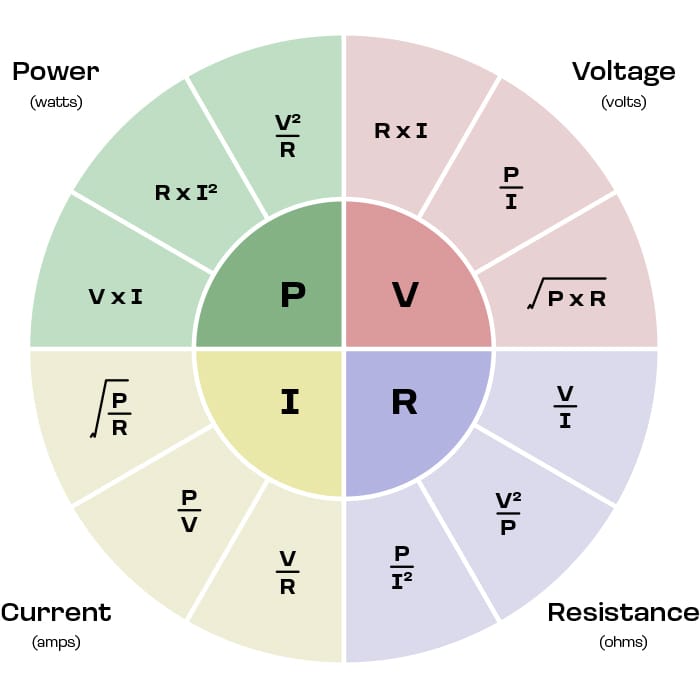

Power is the actual work being done, measured in watts. This is what matters when you’re plugging in your hair dryer or hand mixer. Power is calculated as P = V × I. So a 120-volt hair dryer drawing 20 amperes is using 2,400 watts of power. You’ll also see power expressed as P = I² × R, which is important for understanding heat, something we’ll get to in a moment.

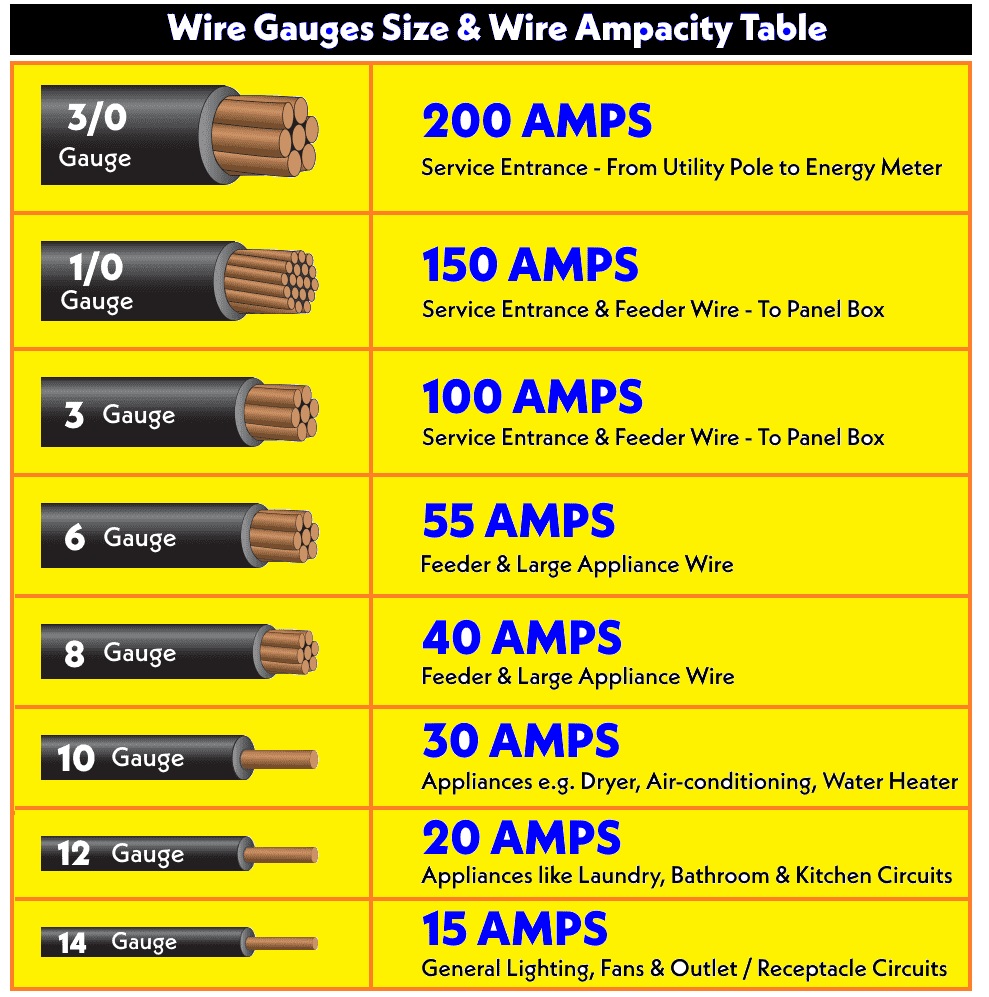

Resistance is the opposition to electrical flow, measured in ohms. Think of it like friction. When water flows through a pipe, a rougher pipe or smaller diameter makes the water work harder to get through. Electricity works the same way. Copper is a good conductor, it has low resistance, but it’s not zero. The resistance of your wire depends on two things: how thick it is (thicker = lower resistance) and how long it is (longer = higher resistance). A 14-gauge wire running 100 feet has more resistance than the same wire running 10 feet. This matters because resistance in a wire creates heat, and that’s what we need to understand next. In residential wiring a 14-gauge wire is rated for 15 amperes maximum, while 12-gauge wire is rated for 20 amperes. That’s the actual constraint. The breaker size must match the wire gauge, or you create a fire hazard.

V = I × R (Ohm’s Law: Voltage = Current × Resistance)

Bring on the hair dryer

Now let’s see how this explains why your breaker tripped, and why you absolutely can’t just buy a bigger one. If you went to one of the home improvement stores to buy a new breaker it would certainly keep that breaker from “tripping”, and thus you’d have no interruption to your crock pot, hair dryer, and hand mixer all on the same circuit. Maybe its better to say, the breaker would not stop you, I do think that there is a real chance the fire you cause in the walls might interrupt you, or what is just as likely you get your hair done, mashed potatoes loaded up in the car, and when the family is driving back to the house from grandma’s you’d notice the fire trucks seeing that the fire might have taken a while to actually start and spread enough to notice before you got out the door.

Critical: The breaker protects the wire not the appliance

Here’s the critical part: the heat generated in the wire isn’t linearly proportional to current, it’s proportional to the square of the current. This is where the danger lives. It goes from 12² × R (144 × R) to 20² × R (400 × R). That’s nearly triple the heat in the same wire. And the wire’s resistance doesn’t change, only the current does. That’s nearly three times more heat for just a 67% increase in current. Your wire wasn’t designed for that. Think about the space heater with a coil of wire that gets red hot, or the old style car cigarette lighters that when you pushed them into the socket glowed red to start a fire. That is what you’re in essence doing inside your wall or attic if you increase the breaker without increasing the wire size.

Here’s what you can do (in order of how much work they are):

- Map out all the outlets to which breaker they are on. Mark the breaker size, location in the panel (or better yet label all). Turn one breaker off at a time and see which outlets don’t work anymore. Then see if there’s a kitchen or bathroom plug that isn’t on that shared circuit.

- Complete the mapping from step 1. Move to another bathroom, or bedroom for the hair dryer. Since that is the heaviest load most likely you can move it. Alternatively, maybe just moving the crock-pot to the dining room or similar would work.

- Adjust timings for the future. Make the potatoes before or after the bathroom getting readiness is in full swing.

- Run a new circuit to the bedroom or kitchen to those plugs. This requires a new breaker (still sized for the wire you’re running), enough wire to run to the wall drops, and some elbow grease. Shut off the main power to the house, fish a wire up from the panel to the attic, run it and terminate either at the wall drops (junction boxes may be required, or straight down the wall to the plugs).

- Decide that after my droning on here you’d rather just call an electrician. ;)

Remember that breakers protect wires not appliances. The breaker box knows nothing about what you connected to it. It simply there to let you know when you’re asking too much of the wire in the wall to safely deliver.